The Lens#6: When the Ears Don’t Cooperate: Quran Learning for Children with Auditory Processing Disorder (APD)

Can Children with Auditory Processing Disorder Master the Quran? Here's How

Understanding the Problem

Auditory Processing Disorder (APD) is a neurological condition where the ears hear sounds perfectly well, but the brain struggles to interpret and make sense of those sounds. In practical terms, a child with APD might hear someone speaking but have trouble understanding the words – especially in less-than-ideal listening conditions. Clinically, APD is defined by deficits in how the central auditory nervous system processes information: children with APD may have trouble localizing where a sound came from, distinguishing similar speech sounds, recognizing sound patterns, or understanding speech in noisy environments. Importantly, APD is not due to any peripheral hearing loss – the child’s ears are healthy – and it’s not due to intellectual or language deficits [1].

The issue lies in the brain’s processing of auditory signals. Current research estimates that APD affects a significant minority of children. Various studies report prevalence rates ranging roughly from 2–7% of school-aged children, though some estimates go even higher [2]. This variability exists because there is no single agreed-upon diagnostic test or criteria for APD, so different studies measure it differently [3]. In one striking example, a 2013 study found anywhere from 7% to 96% of referred children met criteria for APD depending on which tests were used – highlighting the ongoing debate in the field. Nonetheless, a reasonable estimate is that roughly one in twenty children may be affected, which means in a typical classroom or weekend Quran class, it’s quite possible at least one student has APD.

Reported prevalence of APD in school-age children varies across studies. Some large-scale screenings have found rates as low as 0.2%, while other research and expert estimates suggest 3–7% or more of children may have some form of APD. Differences in diagnostic criteria account for the wide range [3].

For parents and teachers, it’s important to recognize the signs and symptoms of APD. Often, these children will act as if they have a hearing loss – saying “What?” frequently or needing information repeated, even though their actual hearing test is normal. They might have difficulty understanding speech in a noisy room or when more than one person is talking [1]. In a quiet one-on-one setting they may cope fine, but add a bit of background chatter or an echoey room, and the child may shut down or respond inappropriately because they couldn’t decipher the words. Children with APD typically take longer to respond to oral communication because their brains need extra time to process what was said [3]. Following multi-step verbal instructions can be very challenging – if you rapid-fire a sequence like “go to your room, bring your notebook, then put on your shoes,” a child with APD might only catch one or two of those steps [12]. They can also be easily distracted by background sounds that others ignore [3]. Some APD signs are surprisingly specific: for example, many of these kids struggle to learn songs or nursery rhymes [3]. That’s because recognizing the lyrics and the rhythm relies on accurate auditory pattern processing – something their brains have trouble with. Similarly, they might have weak phonemic awareness (recognizing and manipulating the sounds in words) which can impact reading and spelling as well. It’s not uncommon for APD to co-occur with other learning or developmental differences; studies show higher rates of APD in children with ADHD or language disorders, for instance [3]. All of this can make the school (and Quran class) experience frustrating for the child. They’re putting in a lot of effort to listen, but what they hear is often incomplete or jumbled by the time their brain processes it.

To illustrate, imagine you’re a child with APD sitting in a bustling classroom or a busy mosque hall. The teacher says a simple sentence like “Please recite the next verse.” But with APD, your brain might not cleanly separate the teacher’s words from the scraping of chairs or the fan whirring overhead. You catch only “…recite…next…,” unsure what to recite next. Or perhaps the instruction “start at Chapter 2, Verse 5” reaches your ears as a garbled string of sounds. This is the everyday reality for children with APD – it’s as if their ears “don’t cooperate” with their brain. Over time, these kids can become anxious about auditory situations or even tune out as a coping mechanism. Notably, APD is often an “invisible” disorder; the child looks and acts completely typical, and can listen normally in ideal settings, so adults might mistakenly label them as lazy, inattentive, or disobedient. In truth, the child is often trying very hard to listen. Their brain is working overtime to decode sounds, which can be exhausting – a phenomenon known as auditory fatigue [13]. By understanding that APD is a real, research-backed diagnosis – with defined diagnostic criteria and even measurable differences in how the brain responds to sound – parents and teachers can replace frustration with compassion. They can move from “why aren’t you listening?” to “how can we help you understand better?”

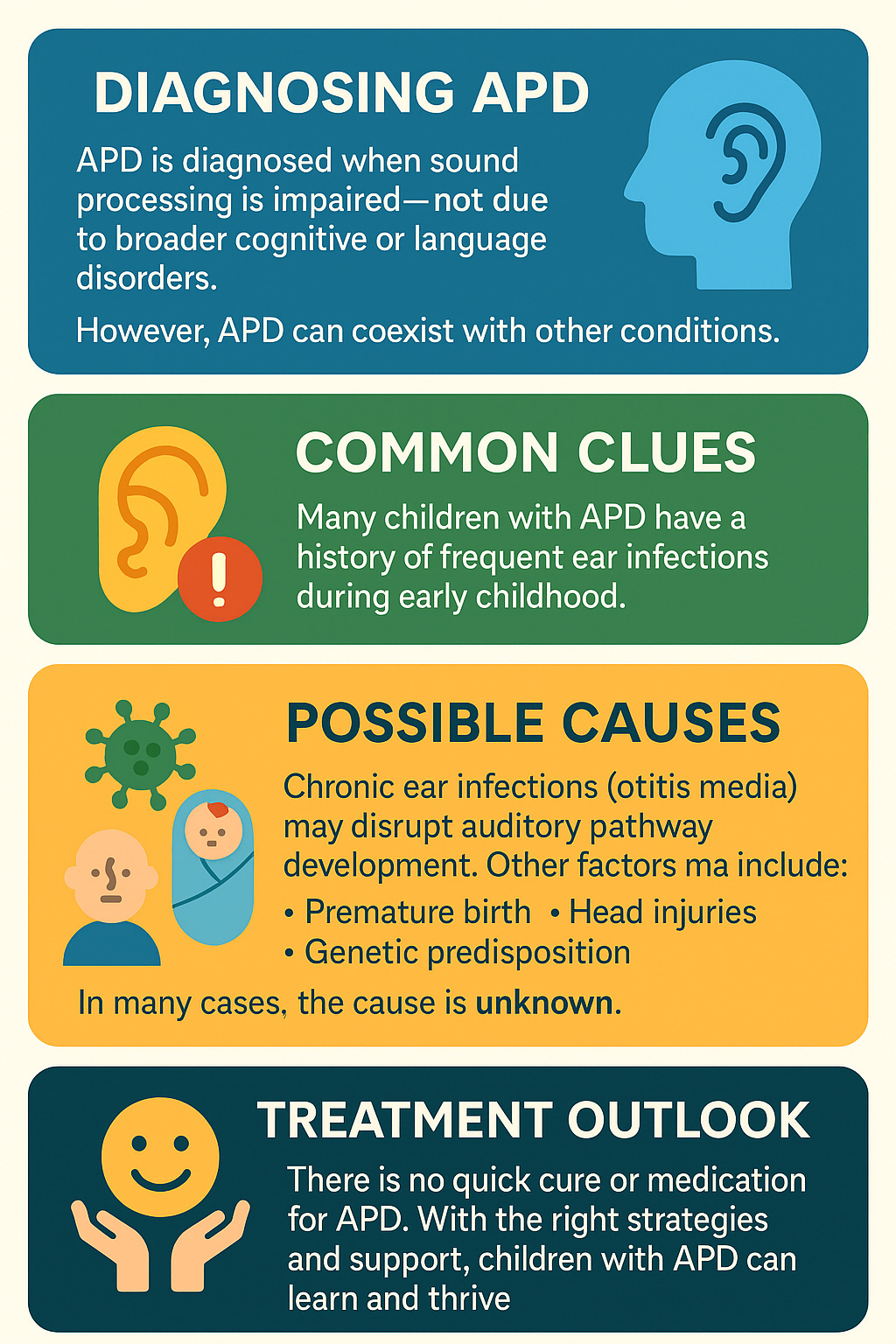

From a clinical standpoint, diagnosing APD involves specialized auditory tests usually conducted by an audiologist. These tests go beyond the standard “beep” hearing test. They might include, for example, listening to words with background noise, identifying differences between similar-sounding syllables, or remembering spoken numbers in sequence. Children are often not formally tested for APD until around age 7 or 8, since younger kids’ auditory systems are still developing. There is no single universally agreed test battery, which as mentioned contributes to varied prevalence rates. However, professionals like audiologists and speech-language pathologists follow guidelines (such as those from ASHA and the American Academy of Audiology) to assess a range of auditory processing skills. Generally, if a child performs poorly (below a certain cutoff) on two or more of these specialized tests and other issues have been ruled out, an APD diagnosis may be given [3]. An important part of the evaluation is also to ensure that any apparent auditory processing difficulty isn’t actually due to something else – for instance, an attention problem or the child not understanding the language. True APD is diagnosed only when the issue is in processing sounds, not a broader cognitive or language impairment (though, as noted, APD can coexist with those). Sometimes a history of frequent ear infections in early childhood is reported in kids who are later diagnosed with APD. Research has linked chronic otitis media (middle ear fluid/infections) to auditory processing deficits – possibly because those early bouts of muffled hearing during critical language periods slightly altered how the brain’s auditory pathways developed. Other proposed causes or contributors include premature birth, head injuries, or genetic predisposition. In many cases, the exact cause is unknown – the APD just is. There’s no “quick cure” or medication for APD [5], but the good news is that with the right strategies and support (as we’ll explore), children with APD can successfully learn and thrive.